(FREE ACCESS) .... WITH VIDEO: MOMENTS TO CHERISH: A “Christmas miracle” — Strangers return fallen soldier’s belongings to family 53 years later

Michael Endicott was a comedian.

That’s what his sister Pat, three years his junior, remembers most about her big brother.

She remembers one December when he was about 12 and the family was worried about affording a Christmas tree.

Young Michael took off on his bike without a word. He came home later, and tied to the back of his bike was the biggest Christmas tree Pat had ever seen. It didn’t even come close to fitting inside their house.

“I will never, ever forget that story,” Patricia Endicott-Werner shared recently during a moment filled with laughter, surrounded by members of her family who had never heard the story and knew very little about her brother. Many of them now live in the St. Louis and St. Peters areas.

Pfc. Michael Endicott was killed in Vietnam at the age of 19, a loss that left deep wounds for his family. So deep, that it was hard for his parents and siblings to talk about him in the years after his death Aug. 5, 1967, in the Quang Nam Province of South Vietnam.

But this Christmas, they’ve been helped to heal a little by strangers from his hometown who knew little about Endicott or his loss when they first took on a project to return a soldier’s belongings to his family 53 years later.

It started with Mary Ann and Chuck Rathe of Poplar Bluff. Mary Ann volunteered the couple to help a friend move on Chuck’s day off. While hauling boxes and furniture, they stumbled across a battered Purple Heart certificate issued to Endicott “For wounds received in action … resulting in his death.”

The friend had found the certificate in a used dresser, picked up at a yard sale.

The Rathes reached out to the Daily American Republic through a friend and asked for help finding his family.

“It’s an honor thing. This poor gentleman died defending our country and he needs to be honored,” said Chuck Rathe.

Endicott is someone who needs to be remembered, and returned to his family in some small way, Mary Ann Rathe said.

“Now, his family has been found. To me, it’s a little Christmas miracle we’ve got going here,” Chuck Rathe said.

The Rathes have helped return more than just the Purple Heart certificate to Endicott’s family.

His sister Pat and his nieces say it is as if Endicott is coming home after more than half a century, because this prompted the family to begin sharing his memories once again.

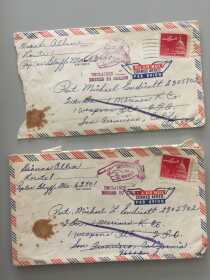

News of the Purple Heart certificate also generated another find, dozens of personal documents, including letters exchanged between Endicott and his family members while he was deployed.

These papers were found by other Poplar Bluff residents in a vacant rental house. Without knowing how to contact his family, the documents were left in the care of the Butler County Archive, which operates from the basement of the Butler County Courthouse.

Members of the archive also saw the article in the DAR and reached out to staff, hoping to return the documents with the Purple Heart certificate.

Endicott’s family believes the papers and certificate were in the care of his mother and were separated from her when she became ill.

The personal papers include a frayed page torn from a 1967 calendar, marking the day Aug. 5, when “Mike was killed in action,” and Aug. 13, the day “Mike came home.” He was buried Aug. 14, in the Sacred Heart Cemetery.

There are newspaper clippings sharing the news that Endicott had graduated from Marine Corps recruit training in San Diego, California, and would return home before his first assignment.

A later clipping reports of Endicott’s death after being injured by a fragmentation explosion from hostile forces while on patrol.

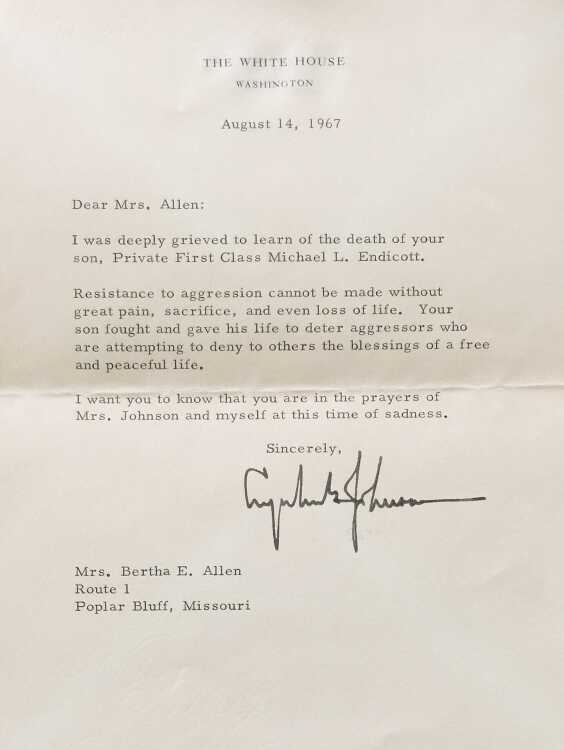

Still in its original envelop is a letter signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson, typed on White House stationary, that reads, “Resistance to aggression cannot be made without great pain, sacrifice, and even loss of life. Your son fought and gave his life to deter aggressors who are attempting to deny to others the blessings of a free and peaceful life.”

A list of Endicott’s effects at the time of his death share that a Rosary was in his belongings, along with photos and letters.

And handwritten letters offer a snapshot for his family of his time in the service.

His mother writes of sending cookies and cupcakes for him, and asks if they arrived okay, and she will send more if they did. She writes about the weather, an upcoming wedding and who has car problems or came by to visit.

Endicott writes back about how hot the weather is, how busy he is, but that he’ll write as often as possible. He tells his family about night patrols, and asks his grandmother to fix some cookies.

Endicott’s mother also saved cards and letters the family received after his death, including a letter written by a Wappapello family she had never met.

The letter came from the mother of a Marine killed two months prior to Endicott, who wrote, “I know your grief and sorrow and there are no words that can ease the grief. It takes time and a lot of prayer to climb up over it.”

The last time Pat saw her brother was in the summer, about a year before his death. He was on leave before he was sent overseas.

The first thing he wanted to do when he got back to Butler County was go swimming in the Black River.

“He threw his duffle bag on the kitchen floor of Granny’s house and changed and off we went,” Pat said during that November get-together with family to share her memories of her brother.

He could talk his sisters into doing anything, she shared, telling another story, this one about the time he convinced them to play in a muddy cow pasture.

“We were just kids. We didn’t know any better. We were horrible, but that was the best time, it really was,” laughed Pat. “I know it sounds disgusting, but that was the best time …. Mike, we would follow him doing anything he said.”

In tearful moments, she also shared that as much of a clown as Endicott could be, he was also a provider, even at his young age.

“He wasn’t that old to get out and earn money the real way, so he did chores for people,” she recalled, and like the Christmas tree, “If we needed something and we didn’t have it, he found a way to get it.”

Joining the Marines was like that for Endicott, she said.

“He wanted to get out away from the poverty and try to make something of himself. I think he was thinking about being a lifer (in the service),” Pat said.

As bittersweet as the memories are, having these items returned, and the opportunity to talk about her brother offered something important — a moment to cherish in 2020.

“He left a mark on a lot of people and they didn’t even know him, but they’re starting to,” said Pat. “I think this has given me a little bit more closure. I just don’t know what to say. It’s helping a lot.”

Her daughter, Joanna Werner, agreed, as did her niece, Longo.

“My cousins and I got to hear these stories for the first time. It’s very neat,” said Longo.

Endicott also has a lot of namesakes amongst both his nieces and nephews who will now get to share in these memories.